Public Domain

By Joseph Mazur

The United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace.[1]

– George C. Marshall, (Unveiling the Marshall Plan, June 5, 1947)

Though cold and hot wars have been with us since the dawn of civilization, the most significant cold one from 1947 to the collapse of the Soviet Union was that between the two twentieth-century superpowers in ideological propaganda competition and economic rivalry. Most significant! Both sides had weapons that could wipe out human civilization and put the world into indefinite darkness. With deterrence enormity on both sides, each played its game coolly, using proxy wars, at other times shadowy ones, but always in an arms race. Cold wars, though, are not as smartly cold as they seem. We are now in a century of wars of various temperatures and battle styles, as well as the ways of proxies and shadows.

War can mean many things. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), the word “war” means “Armed conflict between nations, states, or rules, or between groups in the same nation or state.” However, quirkily, it has expanded to drop the word “armed” and include any hostile conflict of competition or antagonisms between opposing factions. The contemporary definition includes political clashes having almost nothing to do with the active hot wars. Still, wars can be hot, cold, and tepid. And those tepid ones – particularly the political battles – should not be considered simple quarrels; they often heighten to inflict convenient blame that increases temperatures to the level of the OED definition.

By roundabout connections that pass through dangerous escalations, those tepid wars have given us World War One, and, as many expert historians have suggested, the first one brought on a second. All wars start from simple political quarrels, some internal and some from international disagreements that unexpectedly heighten into armed conflict. Wars rarely start without symptomatic warnings, but sometimes they do. The Pearl Harbor attack and 9/11 are just two of the most known examples.

Too often, internal wars spread to become international. Of the multiple internal armed conflicts taking place in the Middle East, North Africa, and Southeast Asia, some are encouraged by intervening foreign powers that pretend not to be involved.[2] Syria is just one example of an internal spillover that became more international than planned.

Uncertified wars, sometimes shadow or proxy, keep arms dealers active and happy since equipment can be on display while avoiding deaths and injuries for the shadow supporter.

With governments reluctant to start hot wars, knowing that gambles and consequences could implode their economies and risk inevitable embarrassments of war crimes, they prefer proxy and guerrilla wars slyly kept in the shadows. Uncertified wars, sometimes shadow or proxy, keep arms dealers active and happy since equipment can be on display while avoiding deaths and injuries for the shadow supporter. The Cold War, one that fortunately had no direct combat between the United States and the Soviet Union, was supposedly fought between competing political policy styles. From one point of view, the issue was almost entirely about preserving or controlling citizenry freedoms. Both sides used threatening propaganda and sometimes subversive punishment directed at their citizenries (McCarthyism and the Stalinism purges).

In a previous article, I wrote about how arms dealing keeps wars coming.[3] All through the years of the Cold War, 56 small battles were ablaze, with contests of weaponry and ideology, partly to keep wars going in a show of equipment for purchase. The wars in Korea, Vietnam, and Afghanistan had different purposes, but they, in roundabout ways, were about weaponry shows.

Remember how the American War in Vietnam started after Ho Chi Minh led and won a war of independence from French control? Following a 1954 independence agreement, Vietnam divided into pro- and anti-communist – North and South – at the 17th parallel. Fearing communist expansion, the United States provided economic aid and military advisors to suppress pro-communist rebels in the South. A decade later, while the United States Navy was on a covert mission collecting intelligence and conducting reconnaissance in the Gulf of Tonkin close to North Vietnam territorial waters, three North Vietnam Navy torpedo boats engaged with a United States destroyer (the USS Maddox). The Maddox fired a warning shot, and one of the North Vietnam boats responded with torpedoes and machine gun fire. One United States aircraft and the torpedo boats were damaged, though four North Vietnamese died. Two days later, an alleged confrontation propelled the United States into the hot war we all know about. An investigation showed that the account of the second conflict – the purported one – was a story concocted by President Johnson and Robert McNamara, the US Secretary of Defense, who used the claim to support retaliatory air strikes and to buttress an administration request for a Congressional resolution that would give the White House freedom of action in Vietnam.[4] Before that Gulf of Tonkin incident, the conflict was essentially internal (save for the spillages into other Indochina territories such as Cambodia and Laos) if we consider the conflicts limited to the two Vietnams. It is an example of how an internal war goes international. In this specific case, as in many others, the spillover inflamed the region by a simple incident that started a second Indochina War.

We learned from McNamara 41 years after the investigation of what happened: “It was just confusion,” McNamara confessed. “Events afterward showed that our judgment that we’d been attacked that day was wrong. It didn’t happen. And the judgment that we’d been attacked on August 2nd was right. We had been, although that was disputed at the time. So, we were right once and wrong once. Ultimately, President Johnson authorized bombing in response to what he thought had been the second attack. It hadn’t occurred.”[5] It was a fiction to have the US Congress grant Johnson the authority to militarily assist countries under communist threats and thereby engage in a war against North Vietnam. Governments play with laws, sometimes creating hot wars from cold ones when they see an ember floating in the wind. If we examine how serious wars start, look no further than the internal conflicts that escalate to turning points that rarely reverse course.

Cold wars are not always so cold

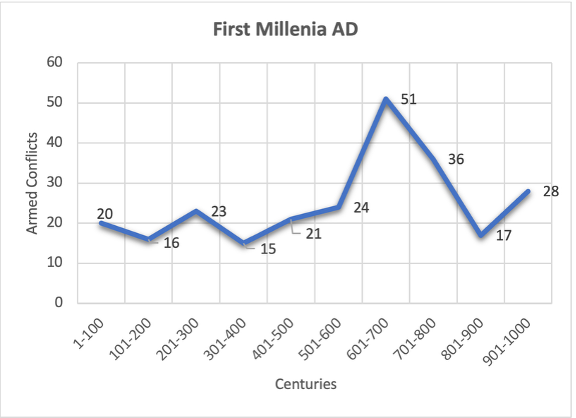

Figure 1. Number of armed conflicts in the first millennium AD

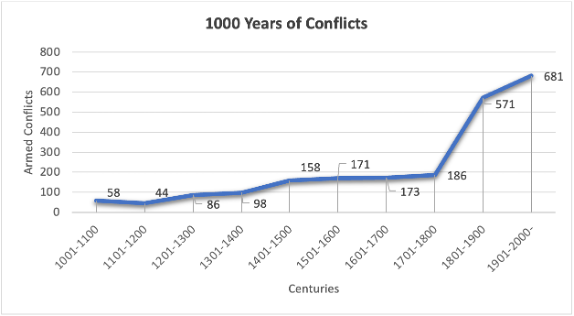

The graph in figure 2 gives a sense of the escalation of the number of wars in the timeline of centuries. Most of those counted are unconventional, involving small groups of rebels, armed civilians, and saboteurs, who bolster internal skirmishes of political battle that explode into full-fledged armed actions that cause enormous civilian casualties. The numbers overlap by spreading and cojoining with other wars, including internal and international skirmishes, political uprisings, coup d’états, guerrilla insurgencies, and proxy wars.

Figure 2. Number of armed conflicts in the second millennium AD

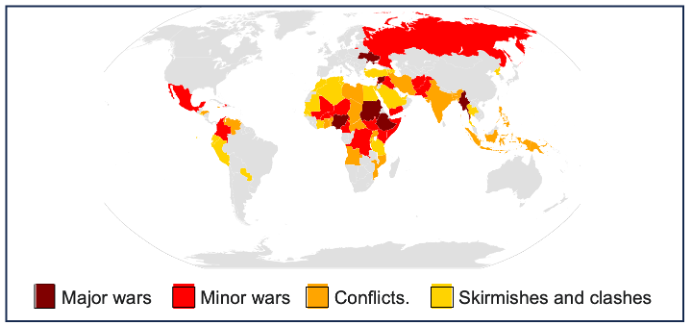

We pay attention to conflicts that we eventually call wars, many of which start small and are urban. If an average informed citizen were to list major and minor battles of the past quarter-century, the list would include no more than 10 of the 25 active recorded armed conflicts. The list would likely include the Russo-Ukrainian War, Syrian Civil War, Israel-Gaza War, Kashmir Conflict, Israeli invasion of Lebanon, United States–Houthis, Sudanese Civil War, Afghanistan, Myanmar Civil War, and possibly the Chad insurgency. However, would those people know anything about the Artsakh War? It is an active war in Azerbaijan that has taken the lives of 190 Azerbaijanis and five Russian peacekeepers, while causing over 100,000 ethnic Armenians to flee the region. It is an example that mimics many – 21 of 25 ongoing armed conflicts in this century, where internal conflicts and insurgencies start as intrastate battles and become proxy wars, meaning they had become supported with military equipment, money, or services from major powers.

Contrast: the world is discovering the slow shifts to proxy wars

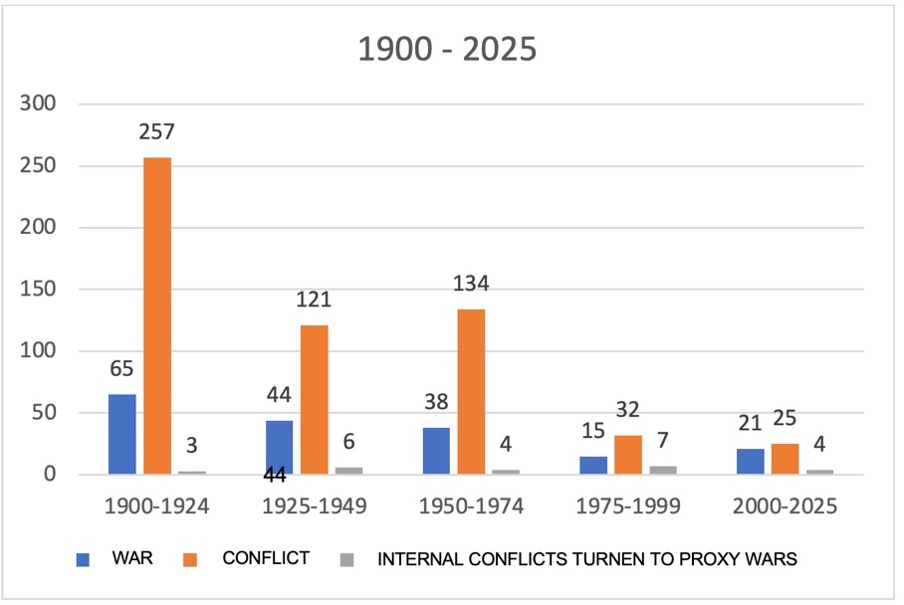

Figure 3. The graph indicates three statuses of conflict.

Conflicts: minor wars, skirmishes both inter- and intrastate that could turn to wars (conflicts includes wars and proxy wars).

Internal conflicts that become proxy wars: wars supported by powerful states.

Domestic wars rarely end heated to the point of being international and hot. Considering wars of the previous century, we find few intrastate skirmishes sliding into interstate wars; however, those interstate wars had very high temperatures (roughly 29.2 million deaths), unlike the ones of this century (approximately 2 million deaths). The Angolan Civil War raged for 27 years. After being colonized by Portugal for 400 years, Angola won independence in 1975. But, with that, a power struggle erupted between the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA), and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA). Cold War communism in Angola spread through the African nations. So, an internal war became a proxy one with the United States, Portugal, and South Africa, inducing Cuba, China, and the Soviet Union to join the fight for political and economic power within Angola.[6] It was a secret and proxy war driven by the Angola engagements of the CIA and KGB.[7] That example is illustratively atypical of civil wars that escalate to international conflicts.

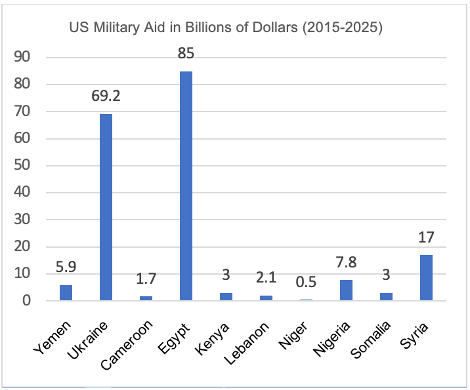

Figure 4. US military support, 2015-2025

Figure 5. Ongoing conflicts.

Source Bullshark44

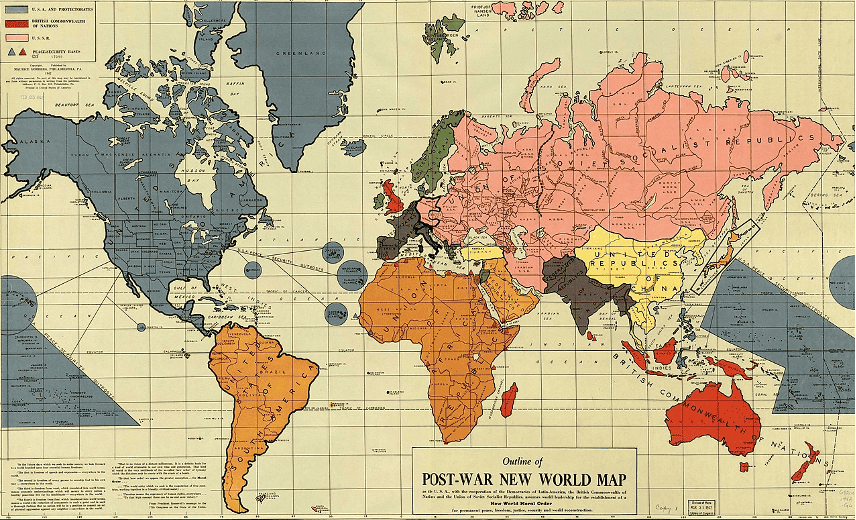

Figure 6. 1942 map of the world showing events of World War II

Figure 7. 1944 map of the world showing events of World War II

The world changes so unforeseeably every half-century

Pick a date and a map of Europe, Asia, or Africa to see border alterations and territory mutations. Maps of every century and almost every continent change frequently through wars, treaties, and revolutions. Flip the pages of the Rand McNally atlas book, The Historical Atlas of Central Europe, for a zoetrope motion illusion, as it shifts boundaries between European countries running in time from the fifth century onwards. In five-color kaleidoscopic reallocations, you will see whole countries disappear as new ones bubble up. In particular, Poland appears as yellow suds of bubbles that pop and expand.

The Korean War

The Korean War started internally as a civil war. The core of understanding it compels a quick flashback to 1904, when the Russian, Japanese, and Korean Empires began long-festering ambitions of acquiring Manchuria because that region of northeast China was a contested territory with valuable natural resources and tactically important for rival empire-building aspirations in Asia.[8] So, Japan invaded Manchuria in 1904, a war that lasted less than a year. From 1910 to 1945, Manchuria was under Japanese annexation. By the end of WWII, when Japan surrendered to the Allies, Korea was divided into two zones that later became separately governed states, each with respective proxy support, the Soviet Union on one side and the United States on the other. It was a Cold War bisection agreement over anti- and pro-communism. Splitting the territory created a clash of governments in favor of reunion, each backed by a strong military and claiming to be the legitimate government of all Korea.[9] When the North invaded the South on June 25, 1950, the United Nations Security Council censured the attack and amassed a peacekeeping force of 21 countries. That war had no benefits to any side in 1953, when an armistice was declared with a secured demilitarized zone (DMZ) to end hostilities claiming the lives of close to 3 million people.

The Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Communist Party won China’s Civil War in 1949 and had a lingering claim on China’s sovereignty over Taiwan. That claim is coming due as China carefully assesses events in Ukraine.

Will China invade Taiwan? That is the towering question following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. We could consider such an act coming from the second phase of the Chinese Civil War (1946-1949), though it might be a presumptive stretch. At the beginning of WWII, China was in a political battle between two parties, the Kuomintang (the ruling Chinese Nationalist Party led by Chiang Kai-shek) and Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party. The war brought the parties together as a coalition team to support the war effort in its fight against the Japanese occupation of Manchuria. After the last world war, the Chinese competing parties were at such serious loggerheads that their attacks escalated to civil war and eventually to the defeat and retreat of Chiang Kai-shek and his Chinese Nationalist Party on October 1, 1949.[10]

Figure 8. Pacific Theater of Operations 1941-45

Public Domain

The debatable question I get from colleagues involved in foreign affairs that often arises whenever Taiwan appears in the news is: Was Taiwan ever a part of China? The answer is complicated, for it’s as if asking if Ukraine had ever been a part of Poland. So, bear with me for a bit of Taiwan history to understand why China might have a right to the ownership of Taiwan. That island has thousands of years of history, with a significant part that happened in the seventeenth century, under Dutch colonial rule, which brought an enormous wave of Southeast Asians emigrating from Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia, a diaspora from Greater China. At the end of Dutch rule, Taiwan was governed by the Tungning Kingdom for a relatively short time before the Qing dynasty, in control of almost all of China, won a decisive naval battle against the kingdom, causing a surrender and occupation of Taiwan for two centuries, by which it became a maritime power controlling sea lanes and coastal areas trading from Southeast Asia to Japan. At the end of the nineteenth century, it was ceded to Japan by treaty after the First Sino-Japanese War.

Figure 9. Map of the Qing Dynasty in 1820, representing its stabilized territory from 1790-1839. (Includes provincial boundaries and the boundaries of modern China for reference.) Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unposted license

Taking over Taiwan will be easy for China and possibly legal by international law. After all, Taiwan was a part of China that was taken away during a civil war and never returned.

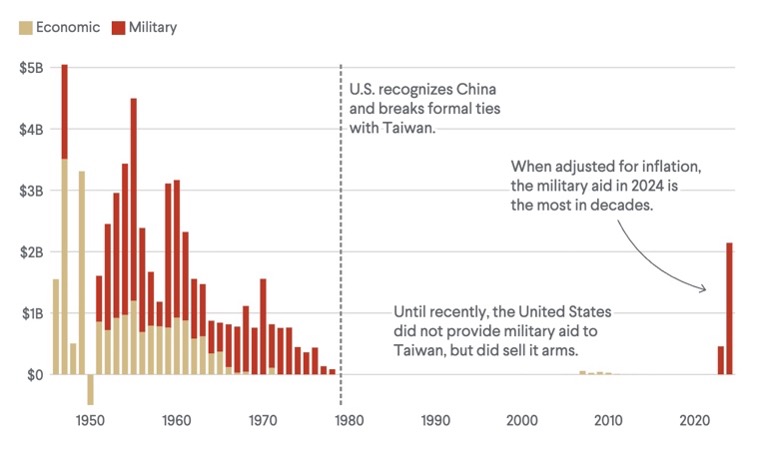

The early twentieth century brought on a decade of revolts that turned into a revolution in 1911, bringing down the Qing dynasty and building a provisional government with a parliamentary republic in 1912, the Republic of China (ROC) ruling as a one-party state for 37 years. Then, immediately after World War II, the ROC lost the Second Chinese Civil War and, by losing control of its mainland governance, was forced to retreat to Taiwan, where it continues to govern, and claim that all of China belongs to its territory. Taiwan is a manufacturing powerhouse, but not a member of the United Nations. That is the nutshell story, but does it tell us anything about China’s island ownership argument? The reason for talking about this now is this: will it take a war to settle the issue, or will the island be ceded to China on the grounds of fairness? Moreover, will China alone attack and occupy Taiwan? Taking over Taiwan will be easy for China and possibly legal by international law. After all, Taiwan was a part of China that was taken away during a civil war and never returned. A Chinese attack on Taiwan could become one of those increasingly trendy twenty-first-century shadow or proxy wars if the United States, which does not officially recognize Taiwan as a country separate from the Chinese mainland, supports the ROC without involving its navy or troops and yet hopes to protect Taiwan while not fully supporting its independence. That lack of support seems contradictory to the military support given for decades before 1980 and in the last two years (see figure 10) while also reassuring China that the United States does not support Taiwan’s independence.[11]

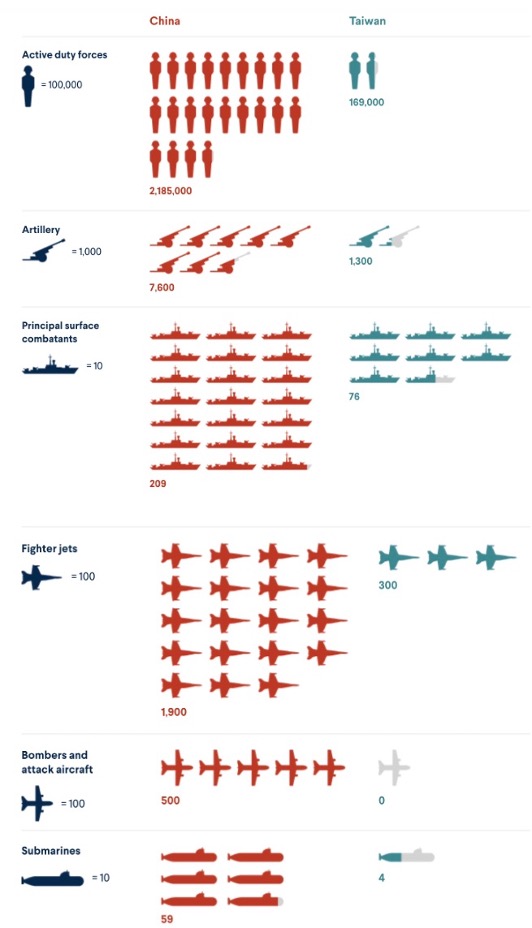

So, the argument becomes this: is it legal for a defeated government party to retreat and govern a territory that is questionably not an officially recognized country? China claims sovereignty over Taiwan, calling it a separatist island, and rebuffs all diplomatic talks. “No matter what the leaders of the Taiwan region say or how they say it,” Chen Binhua, Director of the Information Bureau of the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council said, “it cannot change the fact that Taiwan is a part of China.”[12] With no international laws to help or hinder China’s insistence of sovereignty because Taiwan did not break away by any formal, legal means, Taiwan can be taken by military force grappling with a United States- and Australia-backed war, not a classic proxy or shadow war, but rather something in between, perhaps a shadow of a proxy war with a temperature not cold and not hot, the kind of war by which powerful countries test possibilities of winning territories, minerals, strategical or political influence, by trial. And here we are, with those possibilities rising in the Taiwan Strait with the Taiwan forces at a significant disadvantage against the Chinese.[13] Fortunately, “the second most powerful country in the world rarely chooses to fight the most powerful one.”[14]

Figure 10. Military balance in the Taiwan Strait

Public Domain

Figure 11. US aid to Taiwan by fiscal year, constant 2022 dollars

Public Domain

The conventional US policy has, for decades, been the one deterrent available, which is the presence of the US Navy patrolling in the Taiwan Strait to protect Taiwan and “bolstering Taiwan’s self-defense and enabling offshore US support … the best route to sustaining deterrence while also mitigating the risk of escalation,” though now, there is Donald Trump’s transactional 32 per cent tariff on Taiwanese goods entering the US. But that is another kind of war – transactional tariffs.[15] [16]

Figure 12: Location of Manchukuo (red) in Imperial Japan’s region of influence, 1939.

And now Sudan’s active civil war

Close to three million Sudanese have fled or been displaced to refugee camps or across borders. The situation threatens a hunger crisis far beyond what the world has ever experienced.

Since April 15, 2023, more than 100,000 people have died during Sudan’s power struggle. Close to three million Sudanese have fled or been displaced to refugee camps or across borders. The situation threatens a hunger crisis far beyond what the world has ever experienced. The World Food Programme, the largest humanitarian organization saving and changing lives worldwide, is claiming that “24.6 million people (around half the population) are acutely food insecure, while 638,000 (the highest anywhere in the world) face catastrophic levels of hunger.”[17]

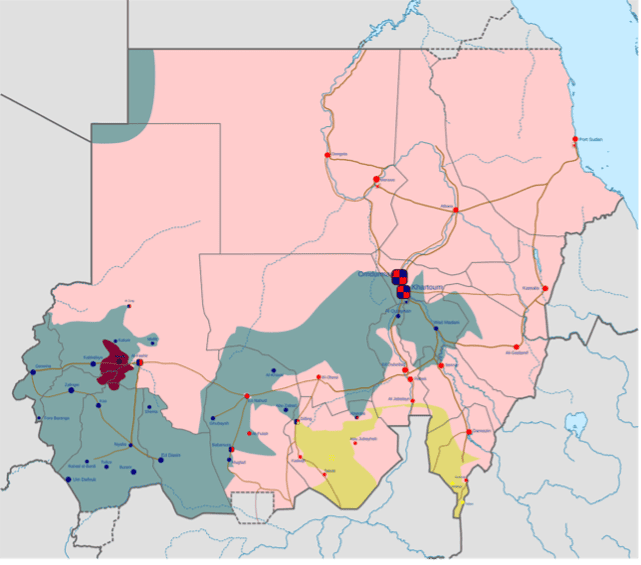

Figure 13. The map of the war of Sudan

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

The United Nations warned that the civil war in Sudan was “spiraling out of control” with fears of a potential cholera outbreak caused by the displacements and instability of the region and its bordering countries.[18] The two sides fighting are the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF), which seized power from the civilian Sudanese government in 2021, and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary force claiming to be a Sudanese parallel government. This latest Sudan Civil War is being fought not only by citizens but also by foreign mercenaries such as the Wagner Group supported by Arab foreign powers such as the United Arab Emirates. Like other civil wars in that region of Africa, there will be other supporting foreign agents and governments that will eventually be involved in internationalizing the war if it does not end soon. The hope is that the United Nations will enforce peacekeeping control to cool down the fighting for humanitarian agencies to bring lifesaving aid to the hungry. Yes, foreign countries could get involved, possibly to swing the war one way or the other. The best is for some sensible country to bring humanitarian aid, which was there before President Donald Trump dismantled the US Agency for International Development (USAID), an agency that, according to the Center for Strategic International Studies, would have saved 750,000 lives.[19]

It is a horrible war, as all wars are, but this one is one of the three worst in this century. Besides having crises of hunger and displacement, the war accepts systematic rape and “dying by suicide to avoid being raped.” [20] It is a war, as each of its civil wars were, about racial hatred derived from the Khartoum slave trading superficially abolished by international treaties in the mid-nineteenth century, yet formally ended just 20 years ago under the Comprehensive Peace Agreement meant to resolve the Sudanese conflicts, and facilitated by eight African states, the United Kingdom, the United States, Italy, and Norway.[21] Like others, it started as a civil war and soon became a proxy one that acquired regional states and the United Arab Emirates secretly supplying weapons to the RSF, while Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Iran were supplying the SAF, both sides disguising their weapons support as humanitarian aid. “Sudan was being forgotten in Washington, partly as a result of the renewed focus on realpolitik from Trump and his America First Cabinet.”[22], [23] I would add the words “bizarrely cruel and vicious” to express Trump and his Cabinet.

United Nations limited control

Figures 1 and 2 show that for two millennia there have been hundreds of hot wars, most of which have devastated huge areas and killed hundreds of thousands and, in some years, millions of people. We seem to tolerate them by permitting governments to continue to operate without significant plans of pre-war diplomacy that could eliminate devastating destruction to human suffering and keep civilians safe. If we imagine a world of intelligent pre-war diplomacy, that picture could spread détente across the continents to benefit all peoples. That was the original promise of the founding of the United Nations. So, what holds back the United Nation’s power to bar wars before they begin? UN resolutions follow a system maintained by the Security Council, a 15-member group of countries, five of which are permanent members. (Note: all five are nuclear-weapon states.)[24] By the UN Charter, all Member States must comply with the Council’s decisions. For enforcement, the Council can impose sanctions on Member States and use force or maintain peacekeeping troops to restore international peace and security.

The UN is the] only fire brigade in the world that has to wait for the fire to break out before it can acquire a fire engine.

– Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan

The UN Charter, Chapter VI, requires states with disputes potentially leading to wars to try to negotiate conciliations through arbitration or judicial settlements. When negotiation fails, clashing states must refer their disputes to the UN Security Council. However, with the veto power of any permanent Member State, peace solutions are rarely approved by the whole Council, because every permanent member supports at least one proxy war.

The United States has enormous oversight regarding conflicts that can ignite wars or expand small ones. With control of at least 750 military bases in 80 countries, and 171,736 active-duty military troops (according to the Pentagon), the United States and the United Kingdom have astonishingly large world military structures that severely dominate any of the other three permanent UN Council Members. With that level of authority, the hope is that decisions as well as vetoes follow moral codes that can otherwise easily drift to national selfishness, political advances, or pure economic exploits. When one or two countries hold the cards of veto power and the world becomes divided into competing priorities, the UN loses its control of commanding détentes and ceasefires.

A new kind of shadow war: call it a ghost war.

If China were to invade Taiwan, would that imbed the region of the South China Sea in a shadow or proxy war? That would depend on whether the Russian invasion of Ukraine became embroiled in a shadow war, which it is if we consider that it is an aggression against NATO, along with sabotage, assassinations, and cyberattacks against Western cities. According to the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA), “Operating covertly and below the threshold of traditional warfare, Russia complicates the tasks of recognition (were we attacked?), attribution (who attacked us?), and definition (are we at war?), without which no adequate response is possible. … Russia’s shadow war targets more than just the physical vulnerabilities of Western economies and societies.”[25] Russia’s attack on Ukraine was not about a shadowy bit of territory to occupy but rather a war of specters hitting the West beyond the frontlines of conventional battle, a war likely to continue and amplify long after Russia finishes with Ukraine’s capitulation, a war of combatants that sabotage infrastructures, mess with power grids, and undermine operations of governing, a ghost war. If Russia succeeds, imagine how popular that kind of war will be. Like the colonial wars of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and like the uptick of the shadow and proxy wars of this century, ghost wars will be the preferences of powerful countries against other powerful countries. Cyberwars are coming. No need for bullets and bombs, tanks, and fighter jets. The dangers behind taking down power grids, airlines, and transportation systems could bring more deaths and destruction than a conventional war.

About the Author

Joseph Mazur is an Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at Emerson College’s Marlboro Institute for Liberal Arts & Interdisciplinary Studies. He is a recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim, Bogliasco, and Rockefeller Foundations, and the author of eight acclaimed popular nonfiction books. His latest book is The Clock Mirage: Our Myth of Measured Time (Yale).

Joseph Mazur is an Emeritus Professor of Mathematics at Emerson College’s Marlboro Institute for Liberal Arts & Interdisciplinary Studies. He is a recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim, Bogliasco, and Rockefeller Foundations, and the author of eight acclaimed popular nonfiction books. His latest book is The Clock Mirage: Our Myth of Measured Time (Yale).

Follow his World Financial Review column at https://worldfinancialreview.com/category/columns/understanding-war/. More information about him is at https://www.josephmazur.com/

Notes

[1] https://www.marshallfoundation.org/life-legacy/

[2] https://geneva-academy.ch/galleries/today-s-armed-conflicts#:~:text=This%20is%2C%20in%20numbers%2C%20the%20most%20affected,Palestine%2C%20Syria%2C%20Turkey%2C%20Yemen%20and%20Western%20Sahara.&text=These%20are%20happening%20in%20Afghanistan%2C%20India%2C%20Myanmar%2C%20Pakistan%20and%20The%20Philippines.

[3] https://worldfinancialreview.com/why-are-there-so-many-wars-especially-now-an-obscure-brilliance-of-arms-dealing-keeps-wars-coming/

[4] John Prados, “Tonkin Gulf Intelligence ‘Skewed’ According to Official History and Intercepts,” National Security Agency Electronic Briefing Book, no. 132 (01 Dec 2005).

[5] https://www.errolmorris.com/film/fow_transcript.html

[6] https://www.menloschool.org/live/files/3479-sammie-floydpdf#:~:text=Not%20only%20was%20the%20U.S.%20getting%20involved,power%20that%20came%20with%20control%20over%20Angola.

[7] https://www.cia.gov/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP88-01314R000100660020-1.pdf

[8] Manchuria was contested because China claimed the region ever since Japan occupied it before WWII.

[9] https://www.unc.mil/History/1950-1953-Korean-War-Active-Conflict/

[10] Kai-shek and his party (at that time called the People’s Republic of China) fled to Taiwan (formerly called Formosa) to govern there.

[11] https://www.foreignaffairs.com/taiwan/taiwan-tightrope?utm_medium=PANTHEON_STRIPPED&utm_source=PANTHEON_STRIPPED&utm_campaign=PANTHEON_STRIPPED&check_logged_in=1

[12] https://www.reuters.com/world/china/anniversary-taking-office-taiwan-president-reiterates-willingness-talk-china-2025-05-20/

[13] https://www.cfr.org/article/us-military-support-taiwan-five-charts

[14]https://oxfordre.com/politics/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-296

doi.org/10.7312/chan20844-006

[15]Oriana Skylar Mastro and Brandon Yoder, “The Taiwan Tightrope.” Foreign Affairs, May 20, 2025. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/taiwan/taiwan-tightrope.

[16] On May 29th a three-judge panel from the U.S. Court of International Trade ruled that Trump’s imposed tariffs lacked “any identifiable limits” and exceed Trump’s authority as president.

[17] https://www.wfp.org/emergencies/sudan-emergency

[18] https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/who-scales-response-following-sudan-declaration-cholera-outbreak

[19] https://www.csis.org/analysis/sudans-humanitarian-crisis-what-was-old-new-again

[20] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2025/05/26/escape-from-khartoum#:~:text=A%20family%20of%20nine’s%20desperate%20attempt%20to%20find%20safety%20in%20Sudan.&text=Like%20most%20civilians%20in%20Sudan,%2C%202023%2C%20was%20a%20Saturday.

[21]https://peacemaker.un.org/sites/default/files/document/files/2024/05/sd060000the20comprehensive20peace20agreement.pdf

[22] Nicolas Niarchos, “Escape from Khartoum – A family of nine’s desperate attempt to find safety in Sudan.” The New Yorker, May 19, 2025.

[23] https://www.foreignaffairs.com/reviews/capsule-review/2017-04-14/realpolitik-history

[24] Permanent members are China, France, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Current members (elected for a term of two years) are Algeria, Denmark, Greece, Guyana, Pakistan, Panama, South Korea, Sierra Leone, Slovenia, and Somalia.

[25] https://cepa.org/programs/democratic-resilience/countering-russias-shadow-war/

#Cold #Hot #Wars #Mixed #Temperatures