By Dr. Willem Schramade

Current corporate finance practices are too narrowly focused on shareholders, resulting in poor outcomes for society, and eventually for shareholders too. But we can embed corporate finance in society, by expressing social and environmental externalities in terms of value. This makes them comparable to financial value, and visible in integrated value and futureproofing ratios that can be used for financial decision making – and ideally policy making too.

Why should corporate finance be embedded in society?

Companies do not operate in a vacuum. They are social vehicles that can exercise power and influence that may exceed that of governments. But they do not bear the corresponding responsibility. Instead, they steer quite closely on their own results and perhaps also to some extent on those of their closest stakeholders. That has major adverse effects, since financial value is created at the expense of social and environmental destruction – to such a degree that societies and political systems are being destabilised.

What goes wrong?

Corporate finance, both as an academic discipline and in practice, is insufficiently embedded in society. The root cause is a narrow view of financial value, which has been propagated by the academic paradigm for decades and which leads to major blind spots.

Financial concepts such as shareholder value and efficient markets have gained enormous traction and have led to great financial value creation, but at an enormous social price. They seemed solid and simple ideas in the vein of Adam Smith’s invisible hand, but they failed in the broader thinking of that same Smith.

Despite the rise of approaches such as sustainable investing, ESG and CSR, etc., there is still insufficient attention to the social consequences and the desirability of business activities, and too much focus on the expected financial value in the short term.

Efficiency is everything, while morality and justice seem to have become secondary concerns in decision-making. We have created a system in which short-term thinking and exploitation are rewarded rather than discouraged; a system in which it has become normal for financial institutions to treat companies as cash machines that need to be squeezed for maximum financial gain, regardless of the environmental and social impacts.

The emergence of such a system was not inevitable, but in retrospect it was likely to happen when we put shareholder value at the core of corporate governance. But there are alternatives.

Then how?

A more broadly oriented and fairer model is possible. For example, steward ownership and family ownership are found around the world and tend to result in longer horizons and better outcomes for society. And historically too, corporations and their predecessors have been run in very different ways than today’s shareholder value mode – as Colin Mayer (2018) describes in his book Prosperity.

In our books ‘Principles of Sustainable Finance’ (2019) and ‘Corporate Finance for Long-Term Value’ (2023), Dirk Schoenmaker and I outline how such alternative models can work financially: how one can weigh social value (S) and ecological value (E) alongside financial value (F), and steer on integrated value: the sum of F, S and E.

We do this using numerous examples and make the calculations for the typical financing and investment decisions, such as DCF analysis, mergers and acquisitions, cost of capital, capital structure, dividends and options. The data may be a challenge, but it can be done.

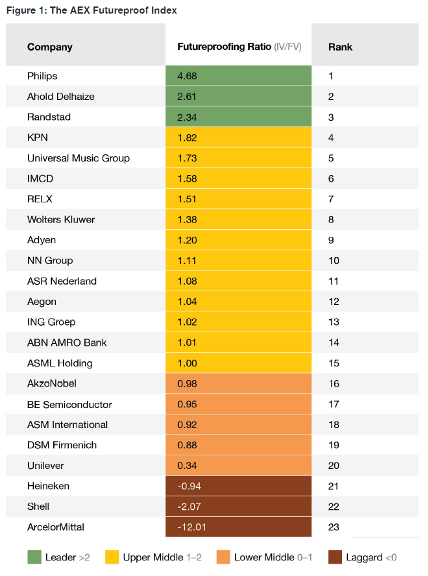

The AEX futureproof Index

We recently launched the AEX Futureproof Index: together with ftrprf and hundreds of students, we estimated the integrated value of 23 companies listed on the Amsterdam stock exchange. We also calculated their futureproofing ratio: integrated value divided by financial value. A futureproofing ratio larger than one means the company has net positive social and environmental value, indicating net transition opportunities. By contrast, a ratio below one indicates that a company faces net transition risks.

We find that collectively, these companies have a futureproofing ratio of 0.7, meaning that they cost society more than they yield: the total financial value of these companies is offset by a negative social and ecological balance of minus 30 percent. However, two-thirds of the AEX companies do make a positive contribution and have futureproofing ratios above 1. The negative total balance is mainly caused by a small number of companies, including steel producer ArcelorMittal and Shell.

Or:

Or:

Or:

Or:

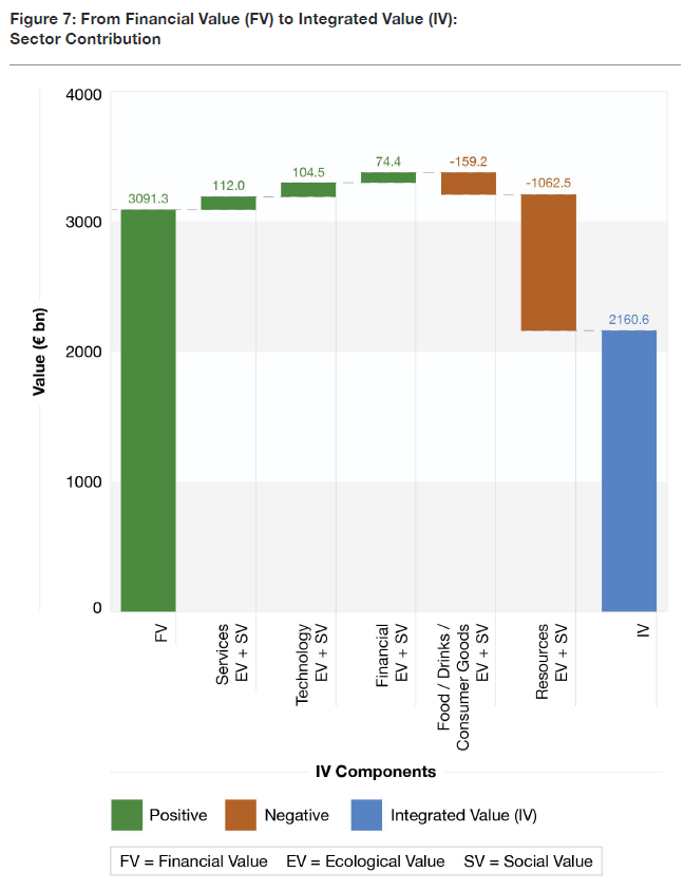

This analysis provides insights into transitional risks and opportunities and the ‘futureproofness’ of business models, offering valuable insights for businesses, investors and policymakers. By far the most negative contribution comes from the resources sector (steel, chemicals, oil & gas – see the picture): more than 1 trillion Euro negative E&S value! So, at first one might think that we’d be better off without that sector (and indeed, that would optically turn the entire index net positive).

But resources are crucial for the rest of the economy, so the better conclusion is: 1) resources offer the largest potential for improvement;and 2) further work is needed to see what improvements could be made at what cost; and measure if resources produced here in the EU have a better footprint than alternatives produced in countries with lower demands on social and environmental performance.

What can corporate leaders and governments do?

Corporate leaders can use this information in several ways. First, they can do this analysis to see where their company, its business units and major products stand; where their competitors stand; and where they have most work to do to become futureproof. Second, this type of analysis can inform their investment decisions, M&A, and financial policies – on which this integrated analysis can shed a surprising perspective. This can be done within the enlightened shareholder value paradigm. But ideally, they embed corporate finance in society and use integrated value analysis to steer on stakeholder value.

Policymakers can play their part too. They can embed integrated value in corporate governance, taxation, regulation, anti-competition policy, etc. Hardcore libertarians might call this socialism, but it definitely isn’t.

This approach is squarely rooted in markets and it fits well with the roots of the EU in the 40s, when Christian-democrats and German ordoliberals designed a social market economy that was meant to avoid the excesses of both socialism and laissez-fair capitalism, to achieve better outcomes for all.

About the Author

Prof. Dr. Willem Schramade is a Finance Professor at Nyenrode, specialising in Sustainable Finance and Investing. With 20+ years of experience, he equips leaders with the knowledge and skills to make long-term, responsible financial decisions. He authored a sustainability-focused finance textbook and has previously held roles at Robeco, NN Investment Partners, and Triodos Investment Management.

Prof. Dr. Willem Schramade is a Finance Professor at Nyenrode, specialising in Sustainable Finance and Investing. With 20+ years of experience, he equips leaders with the knowledge and skills to make long-term, responsible financial decisions. He authored a sustainability-focused finance textbook and has previously held roles at Robeco, NN Investment Partners, and Triodos Investment Management.

#Society #Corporate #Finance #Integration